The livelihoods and cultural identity of Vezo people in southwest Madagascar are intimately intertwined with the marine environment. Vezo livelihoods, however, are increasingly threatened by overfishing and mangrove deforestation, largely driven by demand from outside markets. Climate change is also having an impact, creating inconsistent wind patterns and rough seas too dangerous for fishing. Blue Ventures has been working with partners to pioneer viable alternatives to fishing to support alternative livelihoods, alleviating pressure on fisheries while gaining a new source of sustainable income through lomotse (seaweed) and zanga (sea cucumber) farming.

This series of aquaculture profiles, written by Angelina Skowronski, explores the opportunities for livelihood diversification and capacity building through the eyes and words of Vezo fishers themselves.

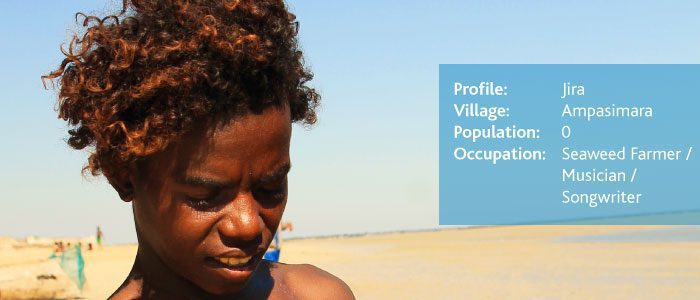

At first glance, Jira looks like an average 22-year-old man. He goes about his day shirtless in basketball shorts, his curly hair bleaching in the sun. One could mistake him for the Malagasy version of a young Justin Timberlake, so it should come as no surprise when he casually mentions that he and his brother, Rojovola, are in a band.

At first glance, Jira looks like an average 22-year-old man. He goes about his day shirtless in basketball shorts, his curly hair bleaching in the sun. One could mistake him for the Malagasy version of a young Justin Timberlake, so it should come as no surprise when he casually mentions that he and his brother, Rojovola, are in a band.

“We’ve written over 60 songs,” Jira boasts, bobbing his head back and forth causing his dark caramel curls to bounce.

Jira is energetic and optimistic, a needed characteristic for his lifestyle. He has two children both under the age of five, and commutes two-hours by foot daily from inland Befandefa to his lomotse farm in Ampasimara. Rojovola and his young wife, Anjarasoa, also make the journey with their 7-month-old.

The young couples exchange carrying the little ones on their backs. One brother carries an axe, which double as a tool for protection and for collecting firewood. The other brother carries a small sack of squid, crab, or rabbit fish; bycatch from the day’s seaweed farming and the family’s dinner.

“We moved to Befandefa after the malaso attack. We never thought of changing lomotse locations because look,” he says, pointing to the shore where the crystal clear water meets the white sun-bathed beach, “there’s nothing better than this sand. Ampasimara has the best environment to farm; the best sand, temperature, and well protected by the harsh winds that rock the ocean outside of the bay. In a way, Ampasimara feels like home because this is where we grew up and where we make our living, but it’s not safe to live here,” says Jira.

Malaso (bandit) attacks are common throughout rural Madagascar. Traditionally, the malaso were cattle rustlers who would solely steal zebu (ox), but attacks have grown into thieving entire villages, ransacking homes, and using violence with weapons. On March 8th 2014, Jira, his family and his village of Ampasimara were victims of a devastating malaso attack that forced the community to flee permanently, dispersing a tight-knit group of successful seaweed farmers.

“When we first started farming, we were making so much money that we didn’t know what to do with it. When you get that much money the only thing you think to do is to spend it all on luxuries,” says Jiro. “After a while we decided to spend it on something sustainable, and started building a house. We had animals, we were well-off, and then the malaso came and took away our livelihoods.”

“When we first started farming, we were making so much money that we didn’t know what to do with it. When you get that much money the only thing you think to do is to spend it all on luxuries,” says Jiro. “After a while we decided to spend it on something sustainable, and started building a house. We had animals, we were well-off, and then the malaso came and took away our livelihoods.”

Jira’s sister-in-law, Anjarasoa describes the attack and her mental inventory of the hard-earned items stolen. “We didn’t know what to do so we just hid because we were scared they would hurt us. They took everything we had, everything in our shop; rice, coffee, flour. We had solar panels, and they took that too. We had to start over,” she says.

Thatched roof huts sprinkling the sandbar characterise these small remote villages of the Velondriake area. Anjarasoa’s shop was no more than her own home; a small one-room hut which housed her, Rojovola and one of Rojovola’s 10 siblings, with a few kilos of staples that she sold to the community cup by cup.

One year after recovering from the malaso attacks that shook the entire Bay of Assassins, the communities of Velondriake were hit again; this time by a larger force.

“The cyclone was saddening. It took everything we had in the water. Rojovola and I were left with a few lines and we shared those among the community to re-cultivate the seaweed,” Jira says; he waves his hand over to where the remaining lines were found.

Seaweed farming is a highly sustainable activity in that the seaweed regenerates itself. Lines can be multiplied easily without the need for a separate grow-out facility. As easy as grow-out is to do, it usually takes three to six weeks depending on the season. After a storm destroys the lines, it could take months before a farmer starts realising a stable income again.

Seaweed farming is a highly sustainable activity in that the seaweed regenerates itself. Lines can be multiplied easily without the need for a separate grow-out facility. As easy as grow-out is to do, it usually takes three to six weeks depending on the season. After a storm destroys the lines, it could take months before a farmer starts realising a stable income again.

“We had to go back to fishing while the lomotse grew,” says Jira. “Fishing only provides money for today and tomorrow, not for the future. Lomotse is more sustainable; you really get to see the fruits of your labour, and you can save for the future.”

Jira describes the effects of the Cyclone Fundi as “saddening” not because of their loss of income, but because “we could not do what we do best,” he says.

Just like land-based farmers have green thumbs, it seems as though Jira and Rojovola have ‘blue’ thumbs for the marine life that they’re able to grow and harvest out of the ocean. They use a small flat-bottom boat, resembling a sledge, to bring in their yield from the sea. The boat is a bonus they received from seaweed buyer Copefrito, for their high production. It brims with green- and red-coloured seaweed on lines. They lace the full lines on a long stick, called tehem-bato, to carry to the drying racks. It is a two-man job, but often the brothers muscle the tehem-bato solo.

After the drying process is completed, taking three days on average, they pack the dried lomotse into 50-kilo sacks. Once a month they transport 4-8 sacks across the Bay of Assassins to Tampolove to sell to Copefrito. The brothers are producing so much lomotse that the transportation of sacks by pirogue alone is usually a full day worth of work.

Their success and love for lomotse is not just evident in their volume of production, but also in their personal creative outlets. They’ve written multiple songs about how lomotse farming has changed their lives.

Herizo, fellow band member and Ampasimara seaweed farmer, describes their passion for lomotse.

“Some people write songs about their cherie (dear) to express their love. We write our songs to express our love for the lomotse. That’s what moves us,” says Herizo.

The trio call themselves Tsy Mialy (No Fighting). They have future plans to make a professional recording and music video in regional capital of Toliara, a 13-hour overnight truck ride atop fish totes.

Already the trio’s talents have made them local celebrities, but they’re committed to not losing sight of their roots. “Even if we were to make it big, we would want to continue lomotse farming,” says Jira. “It is a part of our lives, and it’s not something that we would give up.”

This is the fourth in a series of aquaculture profiles, written and photographed by Angelina Skowronski with additional photos by Garth Cripps, which explore the opportunities for livelihood diversification and capacity building through the eyes and words of Vezo fishers themselves.

You can find out more about our aquaculture work on our website. We would like to thank our partners for their commitment and expertise without which such projects would not be possible.

[vc_button title=”Support our work” target=”_blank” color=”default” size=”size_large2″ href=”https://blueventures.org/support/”]