There was a crocodile in the sea, the legend says.

The crocodile got stuck in a strong current and drifted away, eventually getting stranded on a foreign shore.

There was a boy, the legend says.

The boy saw the crocodile and got closer, for he was brave and kind. The crocodile asked for help, and the boy brought him back to the ocean, where the crocodile prepared to swim away. But before leaving he told the boy:

“I am now in debt with you. If you ever want anything from me call me, and I will come.”

Time passed, and the boy’s feet grew restless, and his heart started to long for the sea. He called on the crocodile.

“I wish to travel. Take me where the sun rises, please.”

And that was how the boy and the crocodile took to the sea, and travelled for many a moon. And then the crocodile grew tired, and had to stop.

“It is time for me to rest, boy. I will now sleep forever, but you can stay with me.”

And the crocodile went to sleep, and his bones turned into rocks, and hills, and mountains. Trees grew on them, and the boy started there a new family, and that is how Timor-Leste came to be.

Timor-Leste’s origin myth is an often-told story, and the first piece of the puzzle in understanding the deep relationship the Timorese – Lafaek-oan, or the crocodile’s children, in Tetun – have with the ocean. This relationship is the frame under which I work when I first start talking to coastal communities about their marine resources.

My ultimate goal is to understand what marine management approaches can work on Atauro Island, but first I need to establish a dialogue with the communities

My ultimate goal is to understand what marine management approaches can work on Atauro Island, but first I need to establish a dialogue with the communities, build a little trust. Talk to people, share food, learn bits of their language. This all takes time. Marine management talks will happen, at some point, later on. I have time. Or so I think.

My first talks, in a few villages on Atauro’s east coast, all follow a certain pattern. We find shelter from the sun under the shade of one of the many trees scattered around the villages, bare feet in the dust, hundreds of tree sparrows flying around us, wrestling scraps of food from the omnipresent chicken. I start with asking about the village – what is the best thing about living here? Answers are consistent. It’s good to be part of a tight-knit community, the feeling of kinship is particularly strong, although at times stained by village politics and old grudges. I move on to the next question, what is the worst part of your community? Again, the answers are consistent, but this time in a manner that surprises me. Every single answer can be traced to insufficient natural resources.

The word for Timorese in Tetun is “Lafaek-oan” or “the crocodile’s children” | Photo: Martin Muir

Communities have been leading a subsistence lifestyle for generations, but things have been changing, resources don’t ever seem to be enough anymore. There’s an underlying tension as people bring their concerns up. Water is scarce, rats are eating all the produce, and of course, fish catches are decreasing.

Coastal communities on Atauro base their livelihoods on subsistence farming and fishing. Men leave their homes early in the morning to fish the most productive reefs surrounding the island.

“The sea is our office, and we have to go to work every day”, one of the fishermen tells me laughing, before he starts describing his fishing methods.

“The sea is our office, and we have to go to work every day”

It’s hard to point out a main technique, or a primary target. Fishing seems to be very unspecialised and opportunistic, multiple gears are used at the same time, and the target is whatever can be found in the water. What is clear though is the deep knowledge these fishermen have of Atauro’s waters.

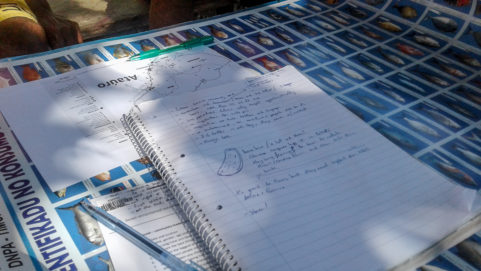

Participatory mapping exercises produce detailed data on the most productive areas for fish, the seasonality of currents, winds, and catches, the deep channels where megafauna can be found. But the data is not just a dry list of coordinates, species and gear. It is interwoven with stories of the past, featuring clever octopus escaping fishermen in their kurita-uma, their octopus-homes in the reefs; accounts of dugong hunting sessions and the fierce battles between man and beast – “I am never going to try to hunt them again, they are too strong,” a fisherman whispers; advice on how you should not fear the saltwater crocodile, as it will only kill you if you don’t have a good heart, or if you cheated on your woman and she has put a curse on you; and of immense schools of large fish darting through the reefs, of fishing days when the whole village could celebrate a plentiful catch.

What is clear in our talks is the deep knowledge these fishermen have of Atauro’s waters | Photo: Martin Muir

“You were lucky if your family managed to eat all the fish you had caught in a day,” I am told by one of the elders of Ilik-namu village, now blind and almost deaf. “It’s not like that anymore,” the other community members quietly mumble, nodding.

Two of the women taking part in this meeting, who have been so far been silent, give a look to their representative. It looks like there is something brewing. The representative takes the floor, and starts advocating for marine management measures that would allow the community to feed their children in the future.

“The women all agree,” she says, “we want a new tara bandu.”

“The women all agree,” she says, “we want a new tara bandu. The other villages already have them, and if we don’t do it too, who’s going to let us fish in their waters when the fish is gone?”

Tara bandu literally means “the hanging law”, as it traditionally involves the hanging of culturally significant items from a wooden shaft to place a ban on certain agricultural or social activities within a given area. They are used in rural areas where the central government is a distant entity, and recently communities in Atauro have been experimenting with using them to create locally-managed marine protected areas (LMMAs).

I know it’s not the first time that this has been discussed in Ilik-namu, and that certain fishermen didn’t respond positively in the past, worried about losing their fishing grounds. But this time the conversation seems to take a different direction. The fishermen appear concerned, and seem to be considering the idea seriously for the first time. Some rapid exchanges in Tetun follow, the women’s representative passionately arguing her case while the fishermen’s body language suggest that they might be accepting that she has a point.

There is a quiet moment after the decision is taken, and then one of the elders turns around and tells me it is time for them to start thinking about the future and managing their marine resources. “We need to discuss with the wider community,” he says, “and make a final decision, but would you be able to support the process?“

Well, that happened way earlier than I expected, but we shake hands as I confirm we would be very happy to.

We have a new LMMA to put together – let’s get to work.

Contribute to critical marine conservation in Timor-Leste as a Blue Ventures volunteer.

Blue Ventures would like to thank our supporters and funders including the Darwin Initiative through UK Government funding, the GEF through UNEP under the Dugong and Seagrass Project, and Wilstar.

Nick, I am so proud and happy to see this processing into local communities taking truly ownership. way to go!

Thanks Najim! And thanks for doing your bit 🙂

‘this is great news, Nick. It bodes well for the Timor Leste program succeeding in the longer term. As a former BV volunteer there, I loved the island, the people and the reefs, and want to see the program help the communities protect their resources.

I can’t commit to a full program, but would love to come for 3-4 weeks fairly early next year. Are you open to that short a participation? I have 7 BV expeditions (1 Madagascar, 1 Malaysia, 4 Belize, and 1 Timor Leste) under my 73 year old belt.

Great to hear from you Roger, thanks for your comment.

Yes, I’m sure that will be possible. Our Expeditions team will be in touch with you shortly.

Glad to hear this Roger! Yes, as Ben said shorter periods are possible. Looking forward to have you on site (again!).

Great blog!! A great way to have more women attending meetings is to supply on-site childcare with a volunteer.