The livelihoods and cultural identity of Vezo people in southwest Madagascar are intimately intertwined with the marine environment. Vezo livelihoods, however, are increasingly threatened by overfishing and mangrove deforestation, largely driven by demand from outside markets. Climate change is also having an impact, creating inconsistent wind patterns and rough seas too dangerous for fishing. Blue Ventures has been working with partners to pioneer viable alternatives to fishing to support alternative livelihoods, alleviating pressure on fisheries while gaining a new source of sustainable income through lomotse (seaweed) and zanga (sea cucumber) farming.

This series of aquaculture profiles, written by Angelina Skowronski, explores the opportunities for livelihood diversification and capacity building through the eyes and words of Vezo fishers themselves.

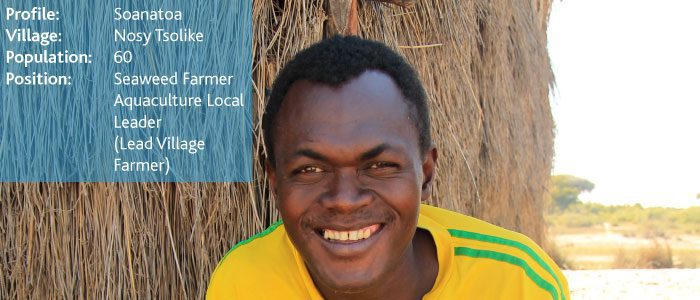

Nosy in Vezo-Malagasy translates to ‘island,’ but Nosy Tsolike isn’t an island. It’s a small village of 60 people on the northern coast of the Bay of Assassins, in southwest Madagascar. Nevertheless, nosy is a good description of the village. It’s remote, surrounded by water on three sides at high tide, and there’s limited access to resources, including fresh water, which residents must fetch from a neighboring village.

Nosy in Vezo-Malagasy translates to ‘island,’ but Nosy Tsolike isn’t an island. It’s a small village of 60 people on the northern coast of the Bay of Assassins, in southwest Madagascar. Nevertheless, nosy is a good description of the village. It’s remote, surrounded by water on three sides at high tide, and there’s limited access to resources, including fresh water, which residents must fetch from a neighboring village.

As he talks, Soanatao draws shapes in the bleached Nosy Tsolike sand with a piece of splintered wood he found in the same spot. He doodles, like one does on a piece of scrap paper while chatting to a friend on the phone.

Soanatao is his nickname, which translates to ‘done good.’ He earned this name as a child because he was always a good boy. ‘Done good’ is seated outside his home, a vondro (grass hut) with low ceilings. He holds the piece of wood delicately like a paintbrush and traces parallel lines in the sand, his newly adopted canvas, while talking about his lomotse (seaweed) farm.

Soanatao is his nickname, which translates to ‘done good.’ He earned this name as a child because he was always a good boy. ‘Done good’ is seated outside his home, a vondro (grass hut) with low ceilings. He holds the piece of wood delicately like a paintbrush and traces parallel lines in the sand, his newly adopted canvas, while talking about his lomotse (seaweed) farm.

“I didn’t buy into it at first. A friend showed me his lomotse farm in Ampisamara. After I went with him to sell the sacks in Tampolove, I realised the benefit and decided to do it myself.”

Before lomotse farming, Soanatao was a shrimp fisherman barely making ends meet to provide for his family of five, the youngest a newborn. “The company gave me the net and I gave them the shrimp. Because they gave me the materials, I was always blamed if anything went wrong,” says Soanatao. “I didn’t have ownership over my work, it was like being an employee of a company, not a fisherman.”

With paintbrush still to canvas, he continues to explain his work as lomotse farmer. “Lomotse farming is different because the farm is yours, and so it’s up to you to take care of it,” he says as he paints over the parallel lines in the sand. “If you take care of it, then you benefit. If you don’t take care of it, then you can’t sell your lomotse and you don’t make money.”

“With shrimp you are paid daily, so it’s easy to spend all the money at once and more difficult to save. You don’t really realise where your money is going that way,” says Soanatao, he takes his paintbrush and pokes the loose sandy canvas now. “With lomotse, you receive a big lump sum once a month. This requires budgeting and saving, so you really get to see where your money goes.”

He and his wife, Fanja run the farm together. He does most of the heavy lifting and she handles the bookkeeping. Fanja attended the CITE training workshops and keeps logs of incoming and outgoing money. Soanatao says that they work as a team, making big financial decisions together.

Their greatest expense is food for the family, then schooling for the oldest child who attends school in district capital of Morombe, a full-day taxi-brousse (bush taxi) ride to the north. School is the easiest to budget because school fees don’t fluctuate month to month, but the food budget is more difficult to predict. “The price of food constantly changes, so it makes it difficult to save. One week rice costs 400 Ariary per kapoky (cup), the next it is 500 Ariary per kapoky. You never know what the price of food will do,” he says.

Soanatao and Fanja don’t keep much in their small home in Nosy Tsolike, not even their bookkeeping cahiers (notebooks). They fear that the malaso (bandits) will one day attack, see the cahiers, and know that they have money saved somewhere.

“We keep all of our money in Tampolove at Chez Richard (local seaweed buyer) so the malaso don’t steal it. We have credit with him,” says Soanatao. He points his wooden brush across the water south towards Tampolove. “We aren’t the only ones that do this. There are a few people in the area that keep their money at Chez Richard. The money is safer there and we trust him.”

There are no banks or financial institutions within miles of the Velondriake area; meaning households must keep their cash in their homes, making them vulnerable to theft from malaso. Malaso attacks are common throughout rural Madagascar. Traditionally, the malaso were cattle rustlers who would solely steal zebu (ox) from owners, but attacks have grown into thieving entire villages, ransacking homes, and using violence with weapons.

With the money safe on the other side of the Bay, Soanatao and Fanja have plans to use their savings to build a trano planche (wooden home) with a tin roof. The grass huts that frame the beachside village of Nosy Tsolike are vulnerable to extreme weather, especially during cyclone season December to March. Building a wooden-sided house is costly, but provides better protection against the elements.

“We want to save money to buy something of worth. Even if this work ends or we run out of our savings because of something unexpected, we want to have a souvenir to show our work’s value,” says Soanatao. He looks to the sand and paints a triangle for a roof and rectangles for windows and doors to the existing parallel lines on his canvas.

I want a clean and healthy village. We don’t have a well. We need to build one, but we need help,Soanatao’s goals are not only personal; he also discusses his wishes for his community. “I want a clean and healthy village. We don’t have a well. We need to build one, but we need help,” he says.

According to an African Development Bank strategy report, Madagascar ranks 112 out of 139 countries for infrastructure quality and spending, translating to nearly half the population living with limited access to safe drinking water. With around 70% of the national budget supported by foreign aid, Madagascar sits in the bottom 25th percentile in the UN Human Development Index.

Despite the comparative rankings stacked against his nation, Soanatao’s goals keep him moving forward. He wipes away his canvas clean and drops the splintered piece of wood to the sand. He puts his four-year-old daughter on his lap. She smiles as if glad to finally enter the conversation after observing patiently from behind her father’s shoulder.

He says cheerfully, “we’re saving for the future, it makes my life feel a lot lighter.”

This is the second in a series of aquaculture profiles, written and photographed by Angelina Skowronski, which explore the opportunities for livelihood diversification and capacity building through the eyes and words of Vezo fishers themselves.

You can find out more about our aquaculture work on our website. We would like to thank our partners for their commitment and expertise without which such projects would not be possible.

[vc_button title=”Support our work” target=”_blank” color=”default” size=”size_large2″ href=”https://blueventures.org/support/”]