Counting octopus, that’s the basic idea. But setting up an octopus fishery monitoring programme is not as simple as you might think. You can’t just hand out some scales and notebooks and then end up with pretty graphs in a few months’ time. That’s why Charlie and I travelled to Indonesia at the start of this year to visit Blue Ventures’ partners there and help them with just this task.

Blue Ventures is currently working with partner NGOs and fishing communities in two sites on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia; sharing our experiences in using management of octopus fisheries to rebuild fisheries yields and as a catalyst for community conservation in the western Indian Ocean. As in Madagascar, octopus is an important commercial fishery for these Indonesian communities who rely predominantly on the sea for their livelihoods.

Before any fisheries management decisions can be made however it is important to fully understand how these fisheries operate. Only with clear and accurate information about octopus catches and the behaviour of the fishers can informed discussions begin about what management tools the communities may prefer to use, and how Blue Ventures’ past experiences can be helpful to them.

Read more about the work of Nusi and FORKANI on Darawa Island

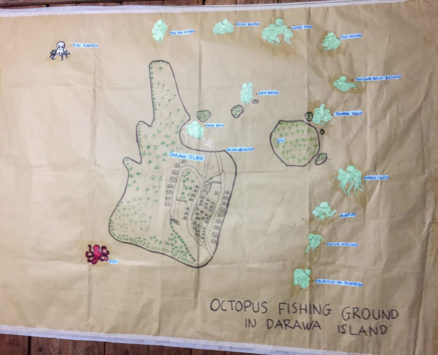

When we arrived in the village of Darawa (within the Wakatobi archipelago, at the far southwestern tip of Sulawesi) we were pleased to see that Claudia, Blue Ventures’ Partnership Support Technician, and Nusi from our partner organisation FORKANI had already begun the process of setting up a monitoring programme. They had employed two local young men as data collectors, fully explained the process to the middlemen (who buy the octopus from the fishers every day) and started spreading the word to bemused villagers about why we were so interested in the octopus fishery!

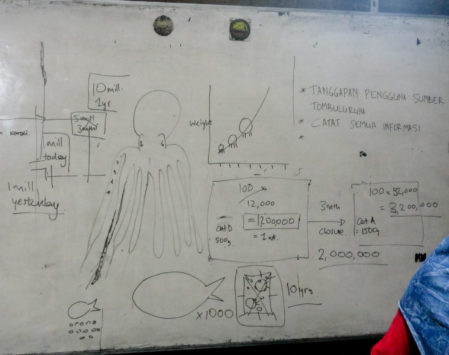

In Darawa there are around 50 fishers who bring their catches to two buyers in the village. This is a very convenient arrangement for the two data collectors, La Tata and La Udin, who can survey all the catches each day at a central point. Charlie and I carried out training on how to weigh and measure an octopus correctly and how to determine its sex. La Tata and La Udin (as well as most of the village’s children) were already a dab hand at doing this in the “normal” way (third leg on the left, look out for a hectocotylus), but Charlie introduced all the techniques needed when the leg is broken or lost. This involves checking the octopus anatomy inside the head and getting very messy with black ink in the process.

As well as data on each individual octopus landed, it is also important to know about the fisher’s activity in catching them so that fishing effort can be taken into account. If a fisher took just one hour of searching to catch two octopus as opposed to seven or eight hours then that tells us something very different about the state of the fishery. To make things more complex it is also important to know about fishers that went out and did not catch any octopus, or only took them home for the pot rather than selling them. So after lengthy discussions with all involved, a set of questions and measures were agreed upon that should provide all the information needed to make informed management decisions, and the data collectors assured us that they were up to the challenge.

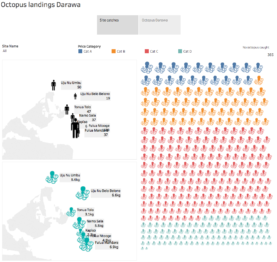

So far so good, but data is of no use to anyone if it just sits in a notebook. Having a simple system to convert recorded data into a state that is easy to analyse is absolutely vital for this type of work. In Darawa we introduced a simple computer form for data entry, designed to be nearly impossible to make a mistake (and if you do it is checked and highlighted), and personalised to fit the octopus fishery data. From there we experimented with different ways of visualising the data – making it more accessible, and more interesting, than a normal bar chart. On presenting these visualisations to the fishermen they seemed impressed, and had many questions about which site yielded the highest catches and who had caught the biggest octopus.

With the successes of Darawa fresh in our minds, we proceeded to the village of Popisi (on Banggai Island, Central Sulawesi) to find just as much enthusiasm for octopus. In Popisi it is the wives of the middlemen that are tasked with data collection, as they already do much of the bookkeeping for their family business. Again, we saw that our partner NGO in the village LINI had already been trialling some data collection, so we offered training to the data collectors to help them perfect their techniques and collect data with high accuracy. In Popisi, as in Darawa, we were met with friendly curiosity and welcome for the project throughout the community.

As Charlie and I took our leave of Popisi we felt confident that our visit has helped to provide these two villages with the skills, tools and knowledge to complete the job themselves. The data they collect will contribute to more informed octopus fisheries management, and we can’t wait to see the results!

All photos in this blog were taken by Charlie, Abigail or Claudia.

Read about how Blue Ventures is exploring the potential for PHE in Indonesia.

Thanks for the great work

Congratulations BV!

Nice work. I’m interested in the fishing gear used there to catch octopus. I have learn that in many places in Indonesia they use artificial baits to catch them. Here in the Yucatan peninsula they also use baited lines to catch octopus, so the management is very different than when they dive for them (as they do in eastern Africa). Please write me with some contact to keep in touch.

Hi Unai, you can find more information here 🙂