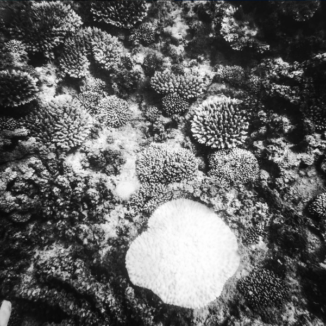

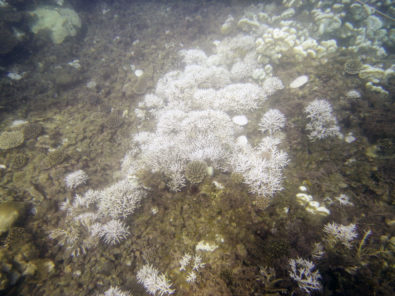

This summer Blue Ventures volunteers and staff in the remote fishing village of Andavadoaka in southwest Madagascar have been enjoying warm waters and calm weather. However, beneath the waves the picture is less idyllic. Where once we dived on reefs that sparkled with the vibrant colours of corals, now we’re finding great expanses of ghostly white. Corals and anenomes here in Madagascar and across the tropics are in the throes of a global bleaching event on an unprecedented scale.

There have been three global coral bleaching events in recorded history, and all have occurred since 1998. The current event began in the western Pacific Ocean in 2014, and is predicted to continue into 2017. It is the longest global coral die-off so far and has now affected some reefs in consecutive years.

But what is bleaching? In order to understand it we first need a quick lesson in coral biology. Corals, both hard and soft, are tiny transparent animals that live together in colonies, each building a skeleton to protect its soft body. They use their tentacles to catch food from the water column, but most of their energy comes from a different source – in an incredible symbiosis, the coral’s tissues are full of single-celled algae called zooxanthellae. These algae are photosynthetic, producing sugars the coral can use from carbon dioxide, water and light. In fact some corals obtain as much as 98% of all their energy from these vital algae. They also give the coral their distinctive colours. Bleaching occurs when the zooxanthellae are lost from the coral and its white skeleton is exposed.

Corals bleach when they experience certain kinds of environmental stress. The leading cause of stress is a prolonged increase in water temperature (particularly temperatures above 30ºC), but pollution, very low tides, strong sunshine and even calm waters are also stressors. These conditions disrupt the delicately balanced relationship between the coral and their zooxanthellae, causing changes the chemicals they produce to go into overdrive and change from useful to dangerous. In large quantities some of the chemicals they produce, such as free radicals, cause damage, forcing the coral to eject them for its own protection.

If conditions return to normal, zooxanthellae can repopulate the corals, but if the ocean temperatures remain too high for too long, the coral will eventually starve and die.

So although we humans have been enjoying the warm, calm seas in Madagascar this season, the corals certainly haven’t. According to the NOAA, climate change and the current intense El Niño are prolonging the longest global die-off on record. In fact, the ten warmest years on record have all occurred since 1998, and corals are unable to cope with today’s prolonged peaks in temperatures. In their recent report the Climate Council of Australia warns that:

“Extreme coral bleaching will be the new normal by the 2030s unless serious reductions in greenhouse gas emissions are achieved.”

Although coral reefs make up only 0.1% of the world’s ocean floor, they provide habitat, spawning and nursery grounds for a quarter of all marine species. Approximately 500 million people worldwide rely on reefs for food and income, and benefit from their ability to protect coastlines from storms and erosion. The importance of coral ecosystems for marine biodiversity and human livelihoods cannot be overstated.

So, can the corals recover? The answer will largely depend on how long ocean temperatures remain high locally. We are still in the grasp of the current bleaching event and, given its extraordinary duration and scale, no one really knows how long it may take for corals to recover from this period of severe heat stress.

In ideal circumstances, bleached corals can regain their colour within several weeks once water temperatures return to normal. However, corals affected by over-fishing, pollution or other stressors are likely to take longer to recover.

Here in Andavadoaka we have witnessed the effects of high ocean temperatures as they have taken hold of our local reefs. We are actively monitoring the situation to better understand how corals are reacting to these conditions, which should help us to predict how fast the reefs will recover. Currently at shallow sites 85% of corals are showing signs of bleaching. However, water temperatures have now begun to fall from a peak of 32°C, so we hope that we have seen the worst of the bleaching this year. Our focus will now turn to assessing whether the corals will bounce back or die as a result of their ordeal.

Look out for more posts about bleaching in future weeks and keep up to date with bleaching in the Western Indian Ocean at http://cordioea.net/bleaching_resilience/wio-bleaching-2016/.

Find out more about our volunteer expeditions in Madagascar, Belize and Timor-Leste

Cover photo: Jen Craighill – Spinecheek anemonefish hovers above a bleached anemone in Timor-Leste