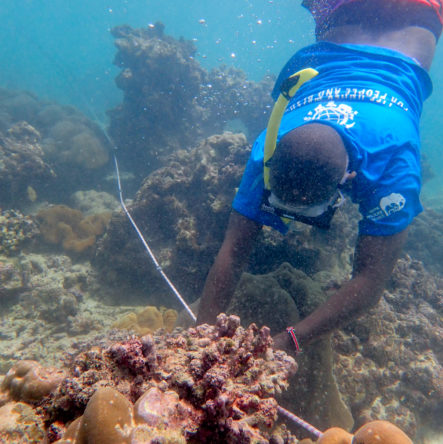

The underwater environments that MPAs seek to protect | Photo: Martin Muir

There are approximately 12,000 Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) around the world, but despite this scale, only 29% of them are regularly assessed for effectiveness. Only 10% of those that have been assessed have been shown to be meeting their goals, but in many cases we just don’t know if MPAs are effective.

Global targets, such as Aichi target 11, often focus on increasing the amount of area of coastal and ocean waters under protection, and MPAs fall under this broad category. In the Seychelles, for example, the government recently announced the final details of 13 new MPAs, making up 410,000 sq km of protected zones covering 30% of the island nation’s waters. Elsewhere in the West Indian Ocean (WIO), other countries are not far behind; Kenya has over 164,000 sq km constituting 15 MPAs and in Tanzania, the 135 MPAs cover more than 241,000 sq km of the surrounding oceans. However, effectively managing these protected areas, both new and existing, takes passion, dedication and a high level of expertise.

At Blue Ventures, we work with small scale fishing communities in a rights based approach that works in parallel with, and in addition to more traditional government managed or co-managed MPAs. But, as I discovered last year, the effective management of these areas should involve everyone at all levels.

In 2019, I met Jennifer O’Leary (Wildlife Conservation Society, Western Indian Ocean region), the co-founder of the SmartSeas Network and co-designer of SAMs (Strategic Adaptive Management for MPAs) now working with MPAs in Kenya, Tanzania and the Seychelles.

SAMs celebrated its 10th birthday in 2019 and from its origins in a few marine parks in Kenya in 2009, the simple approach to improving MPA effectiveness has now been adopted by the Kenya Wildlife service across all five marine parks in Kenya, three marine parks and 15 marine reserves in Tanzania, and is now being adopted by the all four marine parks in the Seychelles.

The approach is a very simple adaptive management process which involves: setting park objectives, monitoring and assessment, management actions based on results of monitoring and areas needing improvement, learning from results of actions and adapting in a cyclical process.

The complex methods used to monitor the MPAs have typically been designed by expert scientists and can be inaccessible systems for the people who deliver park activities day-to-day. The beauty of the SAMs approach is that it is complementary to more scientific monitoring methods; whilst it is in essence, an adaptive management approach used in many industries, what makes SAMs different is how it is done and who is involved.

The SAMs approach is designed to be accessible for everyone in the park so that the whole organisation and wider community learns and grows together

The SAMs approach is designed to be accessible for everyone in the park so that the whole organisation and wider community learns and grows together. From managers to park rangers to community members, everyone gets involved in every step of the process, and it nurtures a culture of passion, innovation and leadership throughout the team.

I first met Jennifer in Kenya in January 2019. With my background in marine ecology, and experience of developing community-based monitoring approaches, she had invited me to join a group of experts in the region to help train and test SAM practitioners from across East Africa so that a community of trainers could be established. The expert groups covered the three areas of strategy and objective setting, monitoring and data collection, data management, analysis and interpretation and by the end of the January meeting we had designed a week-long training and testing curriculum.

Practitioners from three target countries (Kenya, Tanzania, and Seychelles) were encouraged to apply, and we received over 50 applications from the full range of roles within the MPAs from managers, to rangers and community members all of whom had some experience of implementing SAM in their MPAs.

In August I joined the group of nine global and regional marine experts in the Seychelles where we were joined by the practitioners. Our role was to bring 30 MPA staff and community members along in their training and test them on their ability to both use and teach the SAM methods and approach.

From day one, it was inescapably clear that despite wide variation in skills and experience, everyone in the training had a real passion for the SAM approach. They were eager to understand whether their marine parks were achieving their objectives of improving coral and seagrass habitats and increasing the abundance of key fish species.

Our group focused on testing students in monitoring protocols and I was impressed by so many of their stories. One of my students was perhaps most notable – Susan Mtakai, a vibrant young woman from Kenya. When you see Susan in the water you would think that she had been swimming since birth, a real water-baby, but she told me that it was only through SAMs and working with Jennifer that she first learned to swim. After she saw coral reefs and fish beneath the waves for the first time, she never looked back. She is now a competitive swimmer, swimming teacher and lifeguard. She is the first female Divemaster in the Kenya Wildlife Service, and she leads the monthly SAM monitoring within her MPA of Mombasa Marine Park and Reserve. In fact, in Kenya, one key accomplishment of SAM is that the number of park staff who can swim and interact with marine environments has increased from less than 30% to over 80%!

The sessions from the week covered leadership, facilitation and communication skills, strategy and objective setting, monitoring, data management, analysis and interpretation. Students were tested in detail on one area of expertise (either strategy, monitoring, or data) as well as some of the broader themes. At the end of the week all students received a certificate to commemorate their experience. They will continue to do more training and start to support the replication of this approach in other MPAs across the Western Indian Ocean (WIO) as it continues to grow.

Clear objectives allow for clear measures of success. Meanwhile, inclusivity ensures your team is working together to achieve success and can transcend levels of education or organisational hierarchy. These are the key lessons that I took away from my time working with SAMs; both from the other expert trainers, from Jennifer, but most of all from the passionate and dedicated students who are leading their marine parks into the future.

The SmartSeas network and SAMs peer training was funded by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) and the Reef Resilience Network kindly supported the training through the provision of leadership and communications materials.

thanks for the info about this essential component of MBA formation and continuation. And why am I not surprised that Charlie Gough is in the middle (or the leadership) of it! Since I first met her in Andavadoak in 2008, she has been my model for an effective scientist/reef ecologist and energetic leader of volunteers and professionals.