by Olivia Kemp, Fisheries Programme Manager, Madagascar

In August this year, coastal communities in the southwest region of Madagascar celebrated their 10th periodic octopus fishery closure season. Since 2004, villages along this coastline have been annually closing off parts of their fishing sites, and experiencing significant benefits upon reopening in the form of increased catches and incomes. The opening of these reserves is an important event for local communities in southwest Madagascar, and Blue Ventures (BV) was once again there to witness them reaping the benefits of their management efforts.

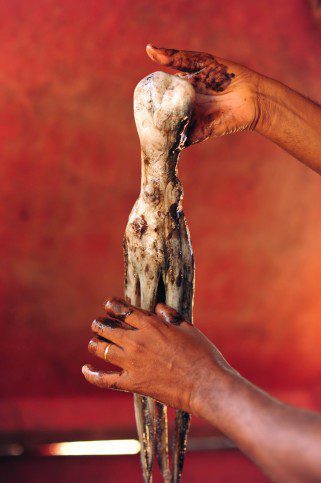

Who knew that one small(ish) cephlapod would be the key to catalysing community engagement in marine management in SW Madagascar!?

Belavanoke, 6am.

Coffee and boko boko, overlooking the bay.

The day dawned quieter than I had expected, with sleepy grey skies and a high tide that kept the reef flats and their octopus out of reach for the next few hours. There had been so much anticipation built over the past weeks of planning and logistics for this day, that now it almost felt surreal as I quietly sipped coffee in the village with my colleagues, waiting for the day to start. Actually if I am completely honest, I had been planning for this day for almost one year, from the day I began my job with Blue Ventures here in Madagascar. The opening of the octopus fishery closures!

As the Fisheries Programme Manager, I coordinate the “octopus project”, as it is usually referred to. The project holds a special place in all of our hearts, as it was in fact the first ever BV project and went on to give birth to multiple conservation initiatives. This is where it all began, with a smart cephalopod and the people who rely on it for survival.

Ten years on and still going strong!

For myself, this was my first experience of really being able to witness the life and blood of my project; to see the fishers bringing in the most important and sizeable octopus catch of the entire fishing year. And perhaps most importantly, to witness these communities managing their fishery in a way that really builds sustainability. These were all aspects of the project that I had spent a lot of my time speaking, writing, emailing, and thinking about, and yet had never really witnessed first hand. I had arrived in the country around 10 months before, and while of course people here fish all year round, (except for the national closure from December to February each year), I had just missed out on seeing the opening of the 2013 temporary closures. But now, the day had finally come for me to be part of it. On the 10 year anniversary of its commencement, no less!

Weighing the day’s catch

Bevato, 10am

At sea, with Humpback whales.

Together with my BV colleagues and the Velondriake Association committee members, we set out at sea in a motorised pirogue, leaving the small village of Belavanoke, to travel over the waves to the island of Bevato. There, a large section of the reef had been closed-off these past two months. On the way there, we received a nice surprise from a small pod of Humpback whales coming up to breathe just near our small boat. It’s moments like these when I feel deeply that I have the right day job. What a morning commute to the office!

An area of reef, chosen by the communities, is closed off for two months to allow the octopus to breed and grow

After 10 years of community outreach and support, most villages in this region are now well experienced in opening their reserves, and so the team and I spent our day observing, rather than actively participating. We believe this has been successful in creating the strong sense of autonomy and ownership that these communities hold over their marine management initiatives.

On the beach of each village or fishing site, community meetings were held prior to the fomba ceremony (a traditional Malagasy ceremony asking the ancestors to bless the event) and the official opening, led by the community elders. When fishing began, it was a humbling experience for me to see. From the very young to the elderly, these truly are people of the sea.

Women are the main stakeholders in this fishery, where they make up over 90% of the total gleaners

In all 13 villages that were opening reserves on the day, BV staff members were involved in varying levels. In some villages, BV staff and expedition volunteers assisted with data collection, sexing octopus and recording total catch weights. In all villages we recorded the number of fishers, pirogues and the number of hours the communities fished for. This information would later help us to determine the catch per unit effort (CPUE). This is a fisheries measurement that helps to monitor the health of a stock that is being fished.

The whole community, from the young to the very old, get involved with the temporary closures

In addition to watching men, women and children glean, catch and sell their octopus that day, I was also lucky enough to witness an exciting step for small-scale fisheries management in this region. In the villages of the Velondriake locally managed marine area (LMMA), a fisher payment scheme has been running for three years now, where the fishers make a one-off weight-based monetary contribution to the management committee when they sell their catch on opening day. The goal of this payment scheme is to facilitate more financial independence for the community associations managing these reserves. Reliance on foreign donor support obviously offers a limited vision and so this model essentially provides an alternative financing option. Costs that may be met by these contributions include phone communications, transport to meetings, the fomba ceremony, and simple materials to demarcate the reserves. Blue Ventures has been supporting the community associations to better understand and adopt this model, and it was rewarding to see it in practice.

To the next decade!

Overall, the day yielded almost 11 tonnes of octopus, with the largest octopus 7kg in size. For me it also yielded a wealth of understanding and a deeper connection with the people I’m working with here. We learned some lessons for next year, and took away some successes also, that hopefully we can continue to share, whether it be with other communities along this coastline, other fisheries around Madagascar or further ashore throughout the western Indian Ocean region. Here’s to the next decade of octopus fishery management in Velondriake and beyond!