By Brian Jones, Conservation Coordinator, Toliara, Madagascar

(Photos by Brian Jones and Jo Hudson)

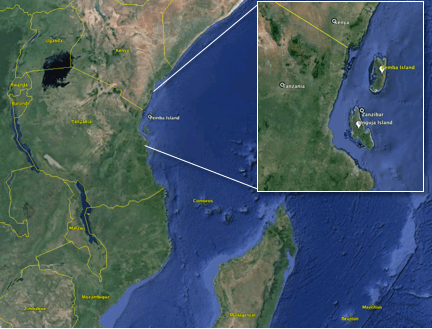

As far as reccie trips go, there are worse places to be sent than Pemba Island, Zanzibar. Though the coast of southwest Madagascar holds a special place in my heart with its turquoise lagoons, deserted beaches and rocky reliefs transitioning seamlessly into the awe-inspiring spiny forest, I wouldn’t have faulted Blue Ventures’ founders if they had chosen instead ten years ago to set up operations on Pemba Island.

Our gracious hosts at the Manta Resort, on the northern tip of Pemba, certainly know how to pick a spot. They tout themselves as a “barefoot luxury resort” and openly admit that it is “not necessarily for all”. Having grown used to staying in budget backpacker hotels in most of my travels, I don’t know who the rest of the “all” are, but this place was decidedly for me.

They wouldn’t let me fire the cannon…

What struck me more than the natural beauty of the area and impeccable hospitality of the Manta team, was the effort they have made to be a standard-bearer for sustainable tourism on Pemba Island. They’ve adopted the “Kwanini” concept, a Kiswahili word meaning “why?” aimed at encouraging reflection on how tourism can develop on Pemba without destroying the special, unique place that it is.

Their extraordinary efforts were recently recognized by Zanzibar’s Minister of Tourism at the official opening of Manta’s new underwater room. On a side note, and at the risk of being overly effusive, this underwater room is truly a sight to behold; a perfect spot for a romantic getaway, or for the curious underwater naturalist who wishes to see tropical ocean life in its natural state, free from the confines of a diminished dive tank and pesky decompression tables.

As we went out for a dive on the second afternoon, I turned around to photograph the resort, only to find that it had essentially disappeared into the landscape, a stark contrast to other resorts which all too often have the look of a father at a college pub: forced, obvious, and out of place.

Where’d the luxury resort go?

Beyond the underwater room, the Manta Resort’s commitment to engaging with the local community and promoting sustainable resource use was more than apparent. Though they’ve made tangible progress, engaging with local leaders regularly in their annual “Kwanini Conference”, piloting alternative livelihood projects like organic gardening, and establishing a no-take zone in front of the hotel, the Manta team still expressed their frustration at the slow pace of progress. This is why they reached out to Blue Ventures; to see if we could draw on our decade of experience of engaging small-scale fishers in community-based management in Madagascar.

Serendipitously, my colleague Jo and I were planning to be in Stone Town, Zanzibar for a community-based aquaculture workshop, and so the Manta Resort offered to bring us over to Pemba for a few days afterwards. Specifically, we wanted to investigate whether temporary octopus closures, which have been used extensively throughout Madagascar, would be appropriate for fishers on Pemba Island.

A “dala-dala” bus heading north, about to get poured on

And so it was that we touched down on a rain-drenched Pemba Island, fresh off our three-day workshop in Stone Town. Neither the torrential rain nor the insufferable young couple who we shared the airport transfer with (that the Manta Resort crew could handle these two with a smile is a testament to their hospitality, to say the least) could dampen our moods as we soaked it all in. The guys at Manta had lined up a number of meetings and village walks for us to help us get our heads around the local context as quickly as possible. With the tireless aid of Haji, a local from Pemba and member of Manta’s hospitality team, as well as Dave, a Kenyan divemaster with seemingly endless passion for the underwater environment, we were able to meet with members of all of the surrounding villages, as well as the head of the fishers association, an independent seafood collector, and a representative of the Pemba Channel Conservation Area (PECCA).

PECCA was high on our list of topics to explore. Established through the Tanzanian government’s Marine and Coastal Environment Management Project (MACEMP), PECCA seems to have made significant progress, establishing a well-known no-take zone near Misali Island, which includes some of the region’s healthiest coral reefs. Unfortunately, in an all-too-familiar story, funding has run out, and revenue from entrance fees is not adequate for PECCA staff to address the myriad challenges the area faces. That said, the fact that they still have active agents who willingly come to meetings and show interest in supporting the development of more community-based management initiatives is more than can be said for some other similar projects in the region.

Focus group with local community members

Through conversations over the three days, we gleaned as much information as possible about resource use patterns, perceptions of the state of fisheries and threats they faced, tenure systems, user rights, conflict resolution mechanisms and existing seafood markets.

Though there are plenty of differences from Madagascar, I was struck by the similarities. “The sea is our life,” was a familiar refrain, coming from Ali Hassan, the head of Shoka village. The words could have been coming out of the mouth of a Vezo fisher in any village on Madagascar’s southwest coast. And again, “But now we’re too many, and the resources are declining. We need other work besides fishing.”

The pressures are the same as well: small-mesh nets, overturning corals and better gear allow fishers to overcome what used to be natural obstacles to overfishing. “Catches have been declining for at least 15 years now,” says Ali, with Mkubwa Saidi, head of the local fishers association, “There has been a lot of destruction to the marine environment here, but the cause of it is poverty. A poor man will do anything to feed his family.”

Ali Hassan (second from left) with some friends by the foundation of a new primary school

Though the symptoms are similar – a rapidly growing population, high dependence on marine resources, markets driving overexploitation, and growing use of destructive fishing practices – the prescription may not always be the same. The temporary octopus fishery closure model has spread quickly throughout Madagascar, but it is not a one-size-fits-all solution to marine management. This model has been popular because resource-dependent fishing communities can see a benefit, in the form of increased catches of the fast-growing octopus, within just a few months. That’s helped to build buy-in for more ambitious marine management measures, like permanent coral reef and mangrove reserves, and bans on destructive fishing.

The quick pay-off is just one part of the puzzle, however. In the case of Pemba, there doesn’t appear to be an engaged, forward-thinking seafood collection company which, in our experience, is a vital component. In Madagascar, octopus reserves have been strongly supported by local buyers Copefrito and Murex, in a common-sense realisation that overfishing is an existential threat to their business model. It is these buyers who are able to soak up a glut, as well as offer a 15% price increase for octopus on opening day, as an incentive to fishers to continue management efforts. They are also working with the local Marine Institute (IHSM) and Blue Ventures to develop an ambitious community-based aquaculture programme, providing a livelihood opportunity alternative to fishing.

Dhows; traditional sailing boats found in east Africa

What there is, however, on Pemba is a community of fishers concerned with the decline in marine resources and ready to take action. There is also a supportive partner in the Manta Resort who, rather than taking the easy path, closing the gates and going self-sufficient, have chosen to become a part of the larger community. They realise that the health of that community is inextricable from their own. We’ll follow the progress of their efforts, and continue to provide support in any way that we can.

The thing about sharing experiences is that it’s a two-way street. Pemba fishers may very well develop management practices that can be applied in Madagascar, Mozambique, Kenya or Tanzania, where traditional fishers are all struggling with similar challenges.

Hotel operators in Madagascar could certainly take a cue on building one of those underwater rooms as well.