The effects of the global COVID-19 crisis are far-reaching, and already being seen by fishing people all over the world.

Even the most remote villages are often connected to distant international seafood markets, selling fish to collectors that travel hundreds of kilometres to buy seafood products for high value export. China and other Asian countries hit first by the coronavirus are amongst the top importers of seafood in the world, and coastal communities supplying these markets were seeing ripple effects of the crisis even before the virus spread to Europe and then Africa. Seafood processors have faced logistical disruptions, as well as a crash in market demand, and many have stopped buying and exporting seafood altogether. In some villages this means that the main source of cash income has been cut off. Tourism is often a key market for demand for good quality seafood, as well as being a common source of employment of coastal communities. Since global travel ground to a halt in March, many people who depend on these markets have also lost their income.

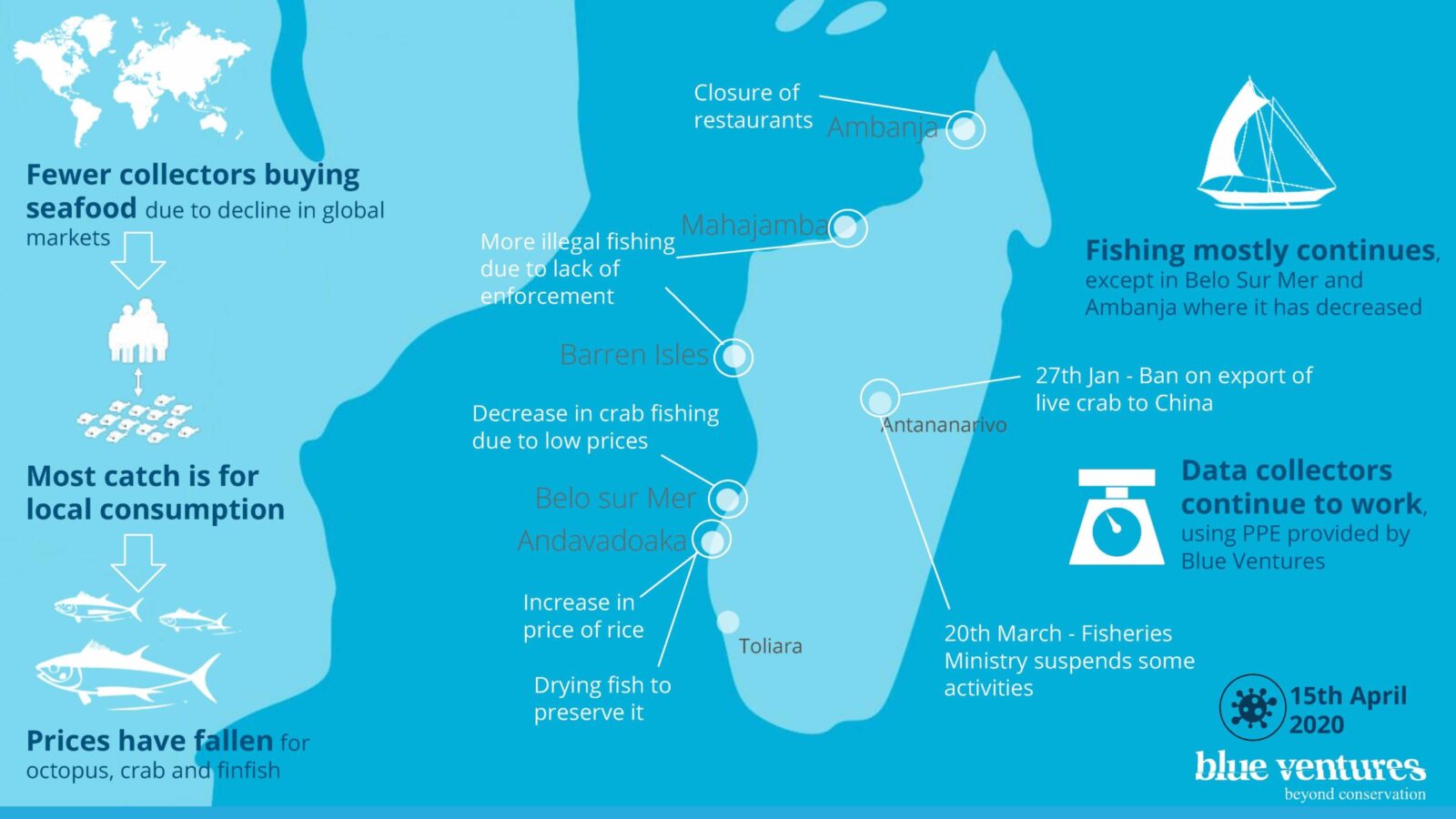

Headline impacts of the Covid-19 crisis on fisheries in Madagascar compiled from observations of Blue Ventures field staff.

Living with vagaries of volatile markets, changing seasons and weather, fishing people are already resourceful and adaptable. In many communities the interruption of export markets and cold chains has led to a resurgence of salting and drying fish for local sale or storage. But the global nature of this crisis is unique, and its duration will be a critical determinant of whether these ‘normal’ coping strategies will be enough to see communities through.

The economic crisis caused by COVID-19 is expected to be severe and long lasting. The crisis will, in many places, deepen poverty. Poverty has immediate impacts – people will be less able to protect themselves and others from the virus or other health issues; as well as long term impacts – it will be much harder for individuals, families and communities to rebound once the acute crisis has passed.

We will also see increased hunger. Fishers often don’t produce their own staple crops, so losing cash income will make them less able to buy essential items like rice. Disruptions to farming and food supply chains that cause price hikes and shortages for staple products will compound this situation, and could lead to widespread food shortages. This could have disproportionate effects on children, that will have repercussions on their development long after the current crisis is over.

As we plan for different scenarios in this dynamic situation, we are conscious of our core strengths as well as our capacity constraints. Blue Ventures is not a humanitarian or crisis relief organisation. In some sites we have a long-established field presence, and in others we are not permanently present on the ground, and instead provide remote support to local partners. In some countries, lockdown measures are making it impossible to connect with, reach or support communities at all.

Womens’ savings group leaders have been trained on how to keep the groups functioning during the crisis whilst respecting health guidelines | Photo: Solontena Raivosoa

Across our various geographies however, we have identified four priorities for supporting coastal communities to deal with the economic shocks related to the global Covid-19 crisis during this precarious time and beyond (our work supporting communities to respond to the health crisis is outlined here):

Understanding the changing situation, and identifying who is most vulnerable to specific shocks

We are gathering data on changes to seafood supply chains and markets, as well as how people are adapting to the crisis. We are synthesising this information to guide our planning, and sharing it with partners and networks to build understanding of the crisis and its impacts on vulnerable coastal communities.

Maintaining services to fishing communities

Now more than ever, we are reminded of the value of the alternative livelihoods that Blue Ventures supports, to help reduce communities’ reliance on capture fisheries. In Madagascar’s Velondriake Locally Managed Marine Area (LMMA), our longest established field site, these now reach almost one third of households across a population of over 8,000 people, with women making up more than half of beneficiaries. We have been able to work with commercial partners to ensure that sales can continue during the crisis, providing critical income to families.

These livelihood activities are complemented by savings and loan groups – low-tech solutions that enable people to save money and access credit where there are no banks. These initiatives are also proving their value in providing a lifeline through hard times. We are working to expand coverage of support for savings groups throughout our work in western Madagascar with partners.

This crisis will increase pressure on marine ecosystems and fisheries, and we are already seeing increases in illegal fishing and mangrove cutting. Where possible, we are maintaining support to community-based monitoring control and surveillance, coordinating with partners and authorities.

In Ambanja, our team supported the local community mangrove patrollers in a mission with the Chief of the Forest Service in the area | Photo: Bienvenue Zafindrasilivonona

Creative problem solving

We are supporting communities as they explore new ways of making money while seafood markets are disrupted. Options being developed include: women’s associations producing cloth face masks to sell locally; finding new local markets for fish; and short cycle market gardening (also contributing to nutrition).

Ensuring fishing communities are on the map

Social protection is key in this crisis, but fishers are often not formally registered, and small-scale fishers are typically low on the agenda of policy makers in distant capital cities. Now more than ever vulnerable fishing communities need recognition of their rights in the face of external threats. We are sharing information and data on fishing communities, including helping authorities identify the most vulnerable people and their needs within relief efforts. Alongside this, we are building strong and nimble partnerships with a range of humanitarian and livelihood support organisations that are well placed to deliver emergency relief where most needed.

A fisherman puts octopus and salted fish out to dry to preserve it | Photo: Garth Cripps

As daunting as this crisis is, we are reassured that our core approach, ways of working and values are already focused on building resilience. We have never had a one-size-fits-all solution to the challenges faced by coastal communities, and an out-of-the-box solution isn’t what is required now. We need to adapt quickly, but we do not need to reinvent the wheel. Our normal way of working – to ‘listen, plan, do, review, adapt, share’ – means we are hard wired to respond to changing local conditions and needs alongside partners, indeed our mission has never been more critical.

Explore our COVID-19 resources for organisations working in community conservation and small-scale fisheries

Read a commentary from our executive director, Dr Alasdair Harris, about the urgency of holistic and community led approaches to conservation