By Jen Chapman, Country Coordinator, Belize

[quote_left]If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

– John Shores, Kinship Faculty, 2014[/quote_left]

It was a busy morning, and I was mildly irritated to hear my phone ring… again! I had been on the phone all morning, and wanted to get my head down to work. My screen showed an unknown number, and I answered wondering whom it could be. To my great surprise and happiness, it was Nigel Asquith, director of the Kinship Conservation Fellows, and he was calling with extremely good news: I been selected to join the 2014 cohort!

For the entire month of July, 19 fellows working in 11 countries descended upon the small town of Bellingham, Washington in the USA (a beautiful part of the world next to the Rocky Mountains), to take part in an intensive programme geared towards training conservation practitioners on the use of market-based tools to achieve environmental outcomes.

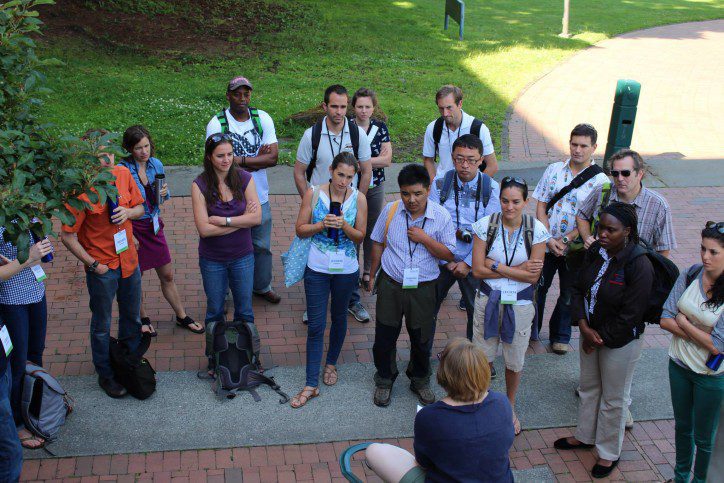

The amazing Cat Rabenstein, Kinship Foundation Communications Associate, conducts an orientation for the group. Image © Matthew King

As the fellows arrived through the day, we were all excited to learn of each other’s diverse work; the list of interesting and diverse projects was amazing, and I felt overwhelmed to be surrounded by so many inspiring people.

The first week kicked off with a debate on the effectiveness using market tools to stimulate positive behaviour change for improved environmental protection. We considered that whilst markets encourage fast innovation and allow a more dignified participation in conservation than regulation, their downfall is they assume all people want to maximise profits, ignoring the intrinsic value of nature. This was countered with the argument that those with a personal interest in conservation will behave in an environmentally conscious way, but those with no interest are motivated by economics – markets provide a means to include more sectors of society into achieving conservation outcomes.

Kinship Fellowship director Nigel Asquith © Matthew King

Greg, a fellow from Emzemvelo KZN Wildlife in South Africa, elegantly concluded the debate with the statement: “It is not that market tools alone are the most effective conservation mechanism, but that the most effective conservation mechanism is one that incorporates market tools.” Later in the course, visiting faculty Ray Victurine and Ricardo Bayon reinforced this whilst discussing the somewhat uncomfortable subjects of nature capital valuation, biodiversity offsets and species banking.

Valuation of species, biodiversity, carbon and wetlands forces the deconstruction of nature to be considered as a direct cost to the project implementer, such as a mining company or property developer. The idea is that once all prevention and mitigation measures have been taken to reduce environmental impact of the development or mine, the company pays a calculated offset amount to be directly invested in measurable conservation outcomes in an equivalent environment. Without this system, such companies have no incentive to reduce impact of their activities or to invest in conservation, whilst demand for their products, including parts in the computer on which I’m writing this blog, continues to rise.

Jen presents to the group on invasive lionfish market development in Belize. Image © Matthew King

During core faculty Ruth Norris’ introduction to the conservation finance conundrum, I was shocked to learn that in the U.S., only 3% of all philanthropic funding is used for conservation, environmental and animal welfare programmes. This is the smallest slice of the philanthropy pie, and is simply not enough to implement all the necessary projects to improve access to clean water, clean air, combat climate change, harvest wild resources sustainably, improve agricultural practices and slow the rate of extinctions. Ruth then gave examples of ways different approaches to overcome this, from Guayaki tea to Blue Ventures’ market based models! I sat proudly in the room as Ruth described how our expeditions operate.

Economics 101 was my first introduction to the subject, and simple concepts of supply, demand and opportunity cost spoke volumes to the needs for accelerated lionfish market development in Belize. It was stressed that in any market, the producers are the economic actors – this means that willingness to pay and demand for lionfish must rise to overcome the risk of lost income that fishers face if they focus their efforts away from high-value and high-demand traditional fisheries such as lobster. Furthermore, an uncoordinated market increases perceived risk even if demand exists: a fisher on the reef doesn’t know if a restaurant in San Pedro is looking to buy or has just bought lionfish, and so this must be weighed in their decision to spend additional fuel to travel to San Pedro and tout their product.

The Environmental Defense Fund’s catch shares fish game was a lot of fun, and will come in handy in Belize!

Understanding what drives human behaviour is central to successful natural resource management interventions, and clearly demonstrated by the Environmental Defense Fund’s catch shares fish game – I had heard of this game being played in fishing communities around Belize as part of the Fisheries Department’s consultation process for managed access, so I really enjoyed finally taking part myself. On a personal level, I was absolutely blown away by the advances in fisheries management in the USA: catch shares and improved fishing methods have removed the race to fish, leading to enormous reductions in bycatch and ever-increasing stocks.

I was most inspired by visiting faculty Christo Marais’ Working for Water (WfW) programme in South Africa, where invasive alien flora reduce water quantity and disturb rivers, leading to excessive sediment load. This has reduced water security and cost the country millions in dam maintenance. With the compounding issue of high levels of unemployment and poverty, WfW combined governmental funds for poverty alleviation with fees collected from water-users to provide training and employment in ecosystem restoration. In doing so, not only are biodiversity and ecosystem services improved, but people are also provided with jobs and the burden of expensive dam maintenance is lessened. This so gracefully shows how intertwined conservation and development needs are.

An icy dip after class at the North Cascades Institute. Image © Greg Martindale

These stimulating classes were interspersed with field trips, where we had the opportunity to explore the beautiful northwest. Each field trip built bonds between the fellows, and I think we all agree that whilst the whole programme was above-expectations-excellent, the best outcome of our time at Kinship was building a new network of professional peers and, beyond that, friends. Friends with a wide range of perspectives, who challenge and encourage, but hold the same values and share the same overall objective: for nature to be valued in and of itself, and to bring that value to the decision-making table.

A massive thank you to all my fellow Fellows, and enormous thanks to the Kinship Foundation and Searle family for such an enriching experience!

Please also read Jen’s interview with Kinship: Creating a Market for Lionfish

Fellows, faculty and the Searle family at the graduation ceremony. Image © Matthew King