This post is also available in:

French

French  Malagasy

Malagasy

As a herd of zebus, the famous Malagasy cattle, passes by the small Blue Ventures’ office in the village of Besakoa, a rumble of hooves means it’s time for everyone to go home. On my computer, I look again at the results of the adult literacy campaign I am coordinating here in the bay of Mahajamba, northwest Madagascar, and feel a glow of pride.

The vast majority (71%) have never been to school in their livesThe learners are all small-scale fishers from the bay and just over half of them are women. The vast majority (71%) have never been to school in their lives, but 93% of those who recently took their intermediate writing and numeracy tests scored above average.

When COVID-19 reached Madagascar, the first phase of the literacy campaign had just ended and our normal course of activities was interrupted. For three months, we worked remotely and prepared for going back to teaching, looking for the best ways to continue the literacy sessions that are so essential for the small-scale fishing communities we partner with in the bay.

Today, the sessions are finally back up and running and the results of the intermediate tests have put a big smile on our faces.

In Mahajamba Bay, our literacy support began just over a year ago. One of the reasons for launching the campaign was a surprisingly low number of candidates when Blue Ventures advertised for community members to train as fisheries data collectors in the bay.

Scientific data informs and underpins decision-making around fisheries, and is essential for the implementation of sustainable local management measures for marine resources. When this data is collected by local community members themselves, it has the potential to become leverage in asserting the rights and ambitions of small-scale fishers and their communities.

We put up posters in all 14 villages of the fishing communities we work with, announcing that we were recruiting and training fisheries data collectors. We had clearly explained the practical details, in the local Sakalava dialect. But weeks passed and to our surprise, some villages had no candidates at all, whilst others had no more than two.

We decided to organise a discussion meeting in each village to listen to the fishers and better understand the obstacles that were preventing them from applying. The explanation was quite simple; the majority of the population in the area can neither read nor write.

For those who could, we adapted the tests to make them more inclusive by reading aloud the questions written on a blackboard to a group of applicants. Eight people were recruited, who showed impressive motivation and commitment to carrying out this essential but demanding data collection work.

But eight data collectors across 14 villages is not many.

We noticed that often, during the tests, when we asked the questions out loud, people from the village who were watching from behind, would also give the right answer. However, they could not be recruited because they couldn’t read and write – essential skills for data collection.

We work in remote areas, where access to education is limited, and opportunities for educational support are scarce.We work in remote areas, where access to education is limited, and opportunities for educational support are scarce. We needed to find a way to overcome this barrier and provide accessible and appropriate literacy sessions for members of these communities, in order to give them the skills they need to manage their own marine resources.

Importantly, this barrier also prevented the wider involvement of small-scale fishers in areas other than data collection. Members of the boards of community associations that manage fisheries resources and mangroves must also be literate, as must community health workers who provide basic health services on a voluntary basis within their villages.

So in September 2019, we launched the literacy campaign here in Mahajamba Bay. Five literacy facilitators from the communities – two women and three men – volunteered to be trained by the local association SOAMANEVA to conduct the two-hour literacy sessions, which ran three times a week in 10 different villages.

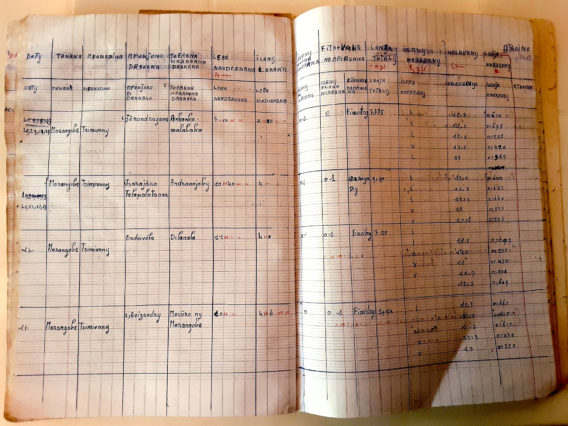

This style of learning means that the learners not only improve their literacy, but also gain knowledge of the environment and natural resources, and acquire basic administrative, organisational and financial management techniques.The facilitators teach functional literacy, which means they give learners the knowledge and skills they need for a specific role and carry out activities for the development of each individual and the whole community. The practical exercises are directly inspired by local marine resource management tasks, such as adding to data monitoring notebooks, filling in budget tables or taking minutes of meetings. This style of learning means that the learners not only improve their literacy, but also gain knowledge of the environment and natural resources, and acquire basic administrative, organisational and financial management techniques.

In the very first sessions, many learners felt ashamed because they were learning the alphabet “like schoolchildren”. But little by little, they built words, and then sentences, and they began to feel proud of what they had achieved – and for a good reason.

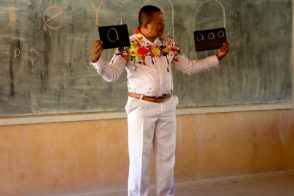

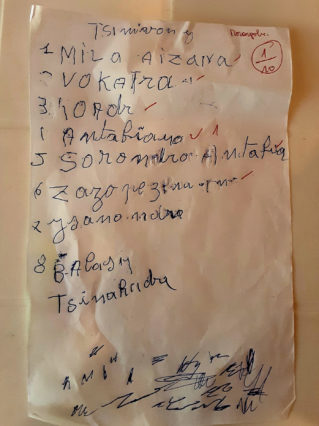

Below is an illustration of the journey of one of the learners. 40 years ago, he had only been able to go to primary school for two years. After being recently chosen to be a data collector, he decided to attend literacy classes to improve his writing (photo 1). 78 hours of literacy sessions later, here is his writing (photo 2). Now, as well as being an active data collector, he is also president of the fishers’ association in his village.

In another village in the bay, one particular story really left its mark; a woman, a member of the community conservation association, used to ask her neighbour to help her write a letter to her children who were away studying in Mahajanga, the regional capital. After attending literacy classes for a few months, she began to write the letter herself for the first time. When the letter arrived, seeing that the handwriting was not the same as usual – that it was neat, very legible and without mistakes – her children called their mother to ask her who had written it. Their mother had to pick up a pen and write in front of their eyes, just so that they could believe it was her – they cried tears of joy at her achievement!

What amazes me the most, is that while 71% of the learners were illiterate, now it feels as if they had never been limited in their ability – they are liberated, and can now take control of their futures.

All the learners are now members of the conservation associations in their respective villages, whereas only 34% were members of the associations at the time they signed up for the literacy sessions. Several are active board members, and three have even become presidents of their local fishers’ associations.

In the world of community conservation, it is rare to see a relatively simple lever for change, with such rapid and concrete positive effects.

Learn more about community data collectors in Madagascar

This is probably on of the best blogs I have read in awhile, it depicts so much progress and I am sure it has not been that easy to achieve. Keep up the good job