The sea around Comoros has been the source of livelihood for Bahati Anli, and many like her in Comoros. She comes from a fishing community and is part of Maecha Bora, an all-women fishers association that leads conservation efforts. When an opportunity came for Comorian fishers to visit Kenya and learn from their peers, Bahati Anli was thrilled to be part of the group that would be participating. This is her experience from the visit.

As the travel day approached, I couldn’t contain my excitement. Not only was I finally travelling to another country for the first time, but I would also witness how other fisher communities interact with the ocean and engage in conservation. I am a fisherwoman, so fishing, octopus gleaning and fish processing are activities close to my heart. When this opportunity came, I was determined to make the most of this trip facilitated by Dahari, COMRED and Blue Ventures.

Despite the language barrier, with many of us speaking Shinzwani and French, I was keen to learn as much as possible. Back at home in Comoros, learning visits are common between communities from different islands, and they present an opportunity to see what peers are doing.

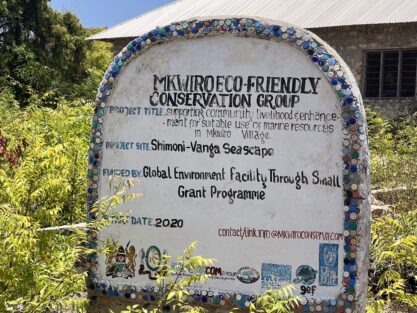

The three-day visit allowed me and fellow fishers from Comoros to learn the different kinds of fisheries management styles used by fishing communities in Kenya and how they engage in conservation.

We got to glean with women from the Mkwiro community of Wasini island, and I noticed they use pointed wooden sticks that don’t damage the reef when fishers target octopuses. A few women in Comoros use the wooden stick, but most still use metal rebars that damage the reef. However, it was surprising that the fishing communities are yet to embrace octopus fishing closures, yet this is a high-value fishery.

While interacting with fellow fishers, I learnt poison fishing is illegal in Kenya, yet this practice is common in Comoros. “It is haram” (illegal), as one community member said.

Despite both countries’ communities being small-scale fishers, fisheries management is different. Fisher associations in Comoros comprise either men or women, like our Maecha Bora association. In Kenya, both men and women are members of the beach management unit in charge of fisher affairs.

It was interesting to see how men and women work together for the benefit of the community. Cooperation among beach management units has allowed the Munje BMU members to set up an octopus fishery closure following a visit to another fishing community in Lamu island, Kenya. I could only imagine how much we could accomplish in Comoros if we cooperated more.

Witnessing how the Kenyan fisher communities manage their fisheries, I couldn’t help but notice that their octopus is smaller than what we catch in Comoros. I wondered how big our octopus would be if we closed larger areas of the reef, seeing that our reefs seem to harbour more and bigger octopus than here in Kenya.

As the trip progressed, I was pleased to see women run alternative income-generating activities to empower themselves. I learnt about a table bank where women involved in conservation lend money to each other and can access loans if they engage in conservation activities such as mangrove restoration and mangrove apiaries where the women expect to harvest honey and sell to earn an income. The women have used the funds to educate their children and build homes, which I want to share with my peers in Comoros.

I came on this trip eager to see what lessons I could take back home to influence my community to manage our fisheries better. I accomplished my mission and am keen to raise awareness back home in Comoros so that men and women can collaborate to implement better fisheries management if it pleases God.

This initiative is funded by the UK Government through ‘The Darwin Initiative’