by Shawn Peabody, Country Director, Madagascar

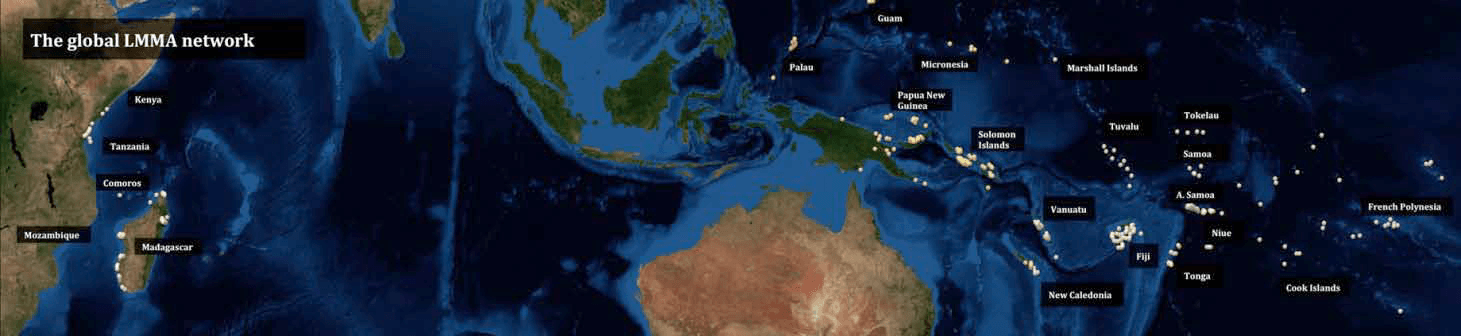

Examples of coastal communities coming together to take on overfishing and reduce destructive fishing aren’t too hard to find. In nearly every region there are good examples of these “positive deviants”, as the literature calls them, where people have figured out ways to work together for their common good. Below is a map showing locally-managed marine areas (LMMAs) in the Indian and Pacific oceans. As you can see, there are hundreds! (to find out more about LMMAs, please click here)

Unfortunately, while examples abound, this isn’t the norm. The vast majority of fishing communities in most tropical developing countries continue to be trapped in a “race to the bottom” where they continue to employ newer, more destructive, and more energy intensive means of extracting as many fish, sea cucumbers, lobsters, or other resources as they can from ever-depleting stocks.

One of the biggest challenges in marine conservation today is figuring out how to replicate the success of the positive deviants at a scale that is ecologically meaningful – across entire countries, regions, and the world. Looking at the history of many of these sites, one sees that much of their success is due to individual leadership, often reinforced and supported by partner NGOs and government authorities. Often the sequence of events leading to the formation of local management groups goes back many years. In some area in the Pacific, a history of local, sustainable resource management goes back thousands of years.

Fisher exchange visit in Andavadoaka, Madagascar 2008. More than 500 fishers have come to Andavadoaka to learn about local management since 2006.

Fortunately, there is a tool that has been very effective at inspiring leadership and spreading the local-management ethos. Fisher exchange trips allow local leaders and fishermen from one community travel to another community to learn about their management techniques and then try to replicate and adapt these strategies in their home communities. This idea isn’t particularly new or revolutionary, it has been tried around the world and been repeated many times over. In fact, many of the LMMAs located on the map above came about at least partly as a result of exchange trips.

However, to date, fisher exchange trips haven’t been studied in any rigorous or systematic way. Additionally, while many organizations have arranged trips and carried out exchanges, there has been very little sharing between those organisations about the results of these trips or how to best organise them.

It is from this context that Professor Kiki Jenkins from the University of Washington, and Hoyt Peking, Director of Smartfish, a marine-focused social enterprise based in Mexico, applied for and won a grant to organise a workshop in Annapolis, Maryland, USA to take a closer look at fisher exchanges. The workshop included leaders from fishing communities who have been involved in exchange trips as well as people from conservation organisations with experience in facilitating and these trips. The workshop was held at the National Socio-environmental Syntheses Center over three days at the end of May.

Participants to the fishers exchange workshop hosted by SESYNC. Blue Ventures Country Director, Shawn Peabody can be found at top-left.

Participants at the workshop shared best practices, lessons learned, and outlined a research plan to formally quantify and improve upon exchange trips. Additionally, they draft a field manual for community leaders and conservation field agents that will be developed further. This manual aims to give useful recommendation for all stages of exchange trips, from choosing participants, to implementation and follow up once fishers return home. A few examples of best practices discussed at the workshop are described below.

- Carefully select diverse group of participants. Aim for a range of fishers, leaders, donor representatives, facilitators, promoters of conservation and ‘non-believers’. Make sure you have some basic criteria (transparent criteria) for selecting fishers and other participants.

- Conduct pre-exchange meeting with participants to emphasize requirements, desired outcomes, and central theme.

- Strive for a combination of hands-on field activities (fishing, diving, games) and informal and more formal discussion time (group meetings, presentations, etc)

- Build into schedules times when fishers can interact with local fishers to confirm experiences heard at the exchange.

- Follow-up after exchange. Have each group of fishers summarize the new information that they’ve gained and how they plan to present it to their communities once they return home.

- Encourage continued engagement among organizers, partners, and participants. Participant contact list should be provided and NGO partners should encourage fishers to reach out to other fisher groups after major new events.

Watch this space for more news on this research and the fisher exchange manual or contact [email protected] if you have questions or want more information.