By Rujinun Palahan (Dream), Seagrass Ecosystem Services (SES) Project Lead, Save Andaman Network (SAN)

I want everything that we have right now here in Koh Mook to continue for our children, for our families and for generations to come.” – Kan Yaprang, fisherman and assistant to the village head

During one of my regular visits to Koh Mook, a small island in the Andaman Sea off the coast of the Trang province, southern Thailand, Kan Yaprang and I were chatting about why conservation is so important to his community. It has been a hot topic in Koh Mook recently, as earlier this month the community took part in an event led by myself and my colleagues at Save Andaman Network (SAN). Through presentations, games and workshops, we supported the community in learning more about their fisheries – in particular, seagrass meadows and the often undervalued services they provide to small-scale fishing communities.

At SAN, we work with coastal communities across Trang to develop locally led fisheries management and marine protection, with a focus on upholding the rights of artisanal fishers. We act as a bridge between government, NGOs and communities to establish partnerships that support community-led conservation efforts and affect policy change. As of January 2020, we are now a partner of Blue Ventures through an International Climate Initiative (IKI) funded project. This Seagrass Ecosystem Services (SES) project is focused on understanding, protecting and restoring seagrass meadows and their valuable services, placing communities central to the development of new locally led research, policy recommendations and community business models that support long-term seagrass and marine conservation.

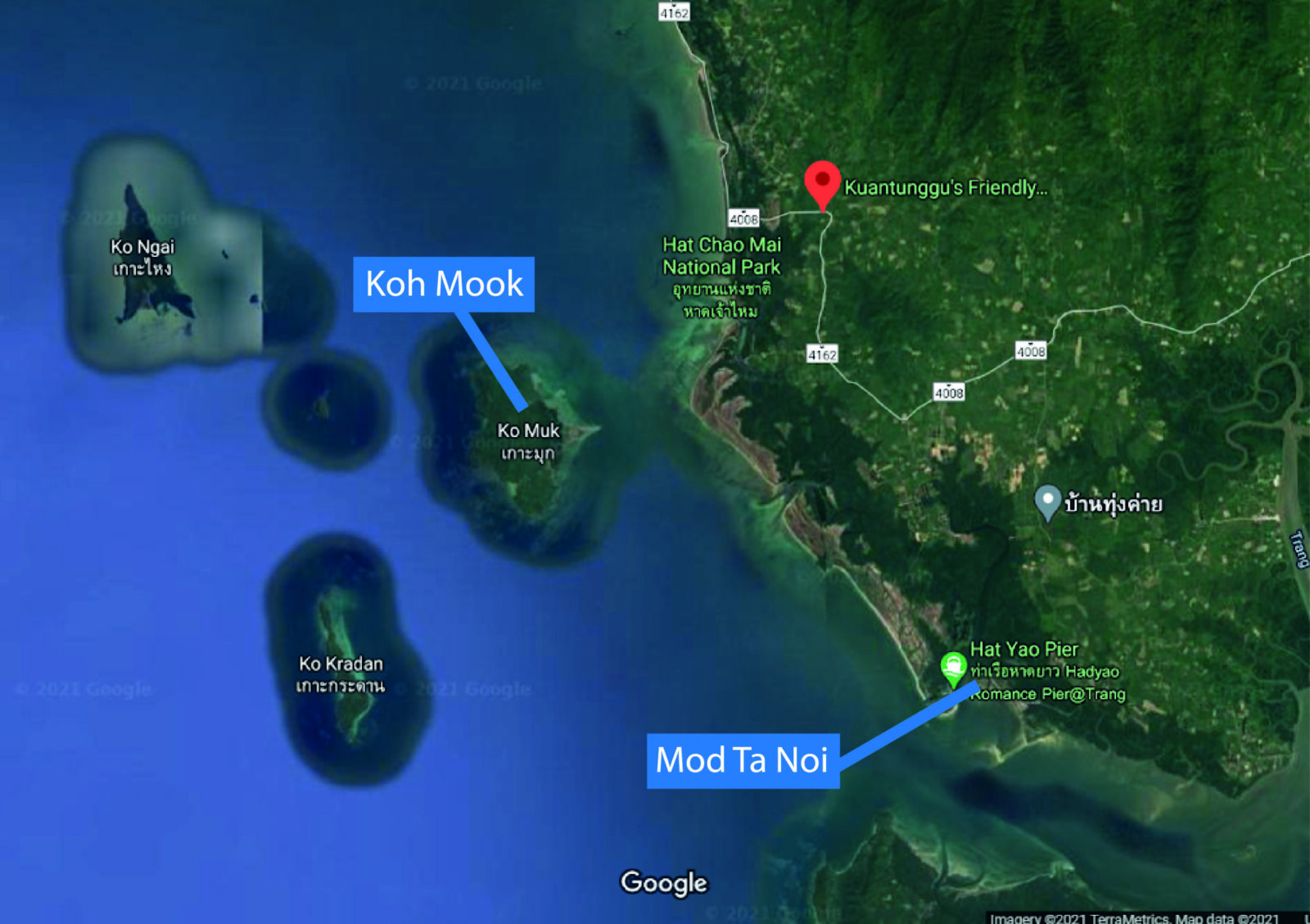

Our interactive seagrass events are an important step in building knowledge and unearthing some of the needs, opportunities and challenges to seagrass conservation from the community perspective. So far, we’ve hosted two – one in Koh Mook and another in Mod Ta Noi, where both communities have rich seagrass areas and a dependency on small-scale fishing.

A map showing Koh Mook and Mod Ta Noi in the Trang province | Image: SAN

Life in the Trang province

Traditionally, most coastal people in Trang are artisanal fishers like Kan Yaprang. Men fish and women work throughout the value chain, in seafood processing or selling at local markets.

Like much of Thailand’s coastlines, the area is famed for its natural beauty, with rich turquoise waters decorated with green islands framed by white sand beaches. But unlike more well-established tourist hotspots like Krabi and Phuket, Trang is largely unknown to international visitors, mostly welcoming Thai tourists who enjoy a quieter, more community-focused experience. The communities here are increasingly interested in developing their tourism operations whilst staying true to their regional, community and religious values. Through locally led tourism enterprises, the communities in both Koh Mook and Mod Ta Noi offer boat tours and excursions that support many alternative livelihoods.

In Mod Ta Noi, the community have been investing their tourism earnings in supporting marine conservation efforts and community development, and in Koh Mook, there’s a desire to follow a similar path.

For decades, commercial and illegal fishing has put a strain on the ecosystems that the communities here rely on. In December 2004, the devastating tsunami that thundered across the Indian Ocean compounded this pressure, destroying many of Trang’s marine and coastal environments. This is when our team at SAN began working with communities in the area, supporting them to restore damaged infrastructure and rebuild lost livelihoods. Since then, SAN has also supported them in addressing illegal fishing, as well as raising awareness of dugong protection and mangrove and seagrass conservation.

Amongst Trang’s artisanal fishing communities, seagrass is an integral part of daily life, “It is our source of food and livelihoods, and so it gives us our quality of life”, Kan Yaprang told me. The seagrass meadows are where he catches fish, shellfish and shrimp to feed his family and to sell at markets. By earning money from seagrass-related livelihoods, fisher families can share their earnings around without having to invest time in other supplementary livelihoods. In Koh Mook and Mad Ta Noi, where most residents are Muslims, this means having more time to practice their religion and maintain a higher quality of life. Here, seagrass is more than just food and jobs – it enables the community to uphold its cultural identity.

Learning through play

From seafood processors and boat captains to school students and representatives from holiday resorts, we welcomed over 60 community members in Koh Mook and Mod Ta Noi to March’s seagrass events. We invited a diverse set of people because whether their livelihoods operate directly in the ocean or not, we believe that all of them are connected to seagrass in some way. It was amazing to see community members listening to each other’s perspectives and recognising that they all share the same goal to protect their environment.

In both villages, the events were action-packed – we led training presentations, held workshops and in Koh Mook, we supported community members to participate in seagrass monitoring. The school students particularly enjoyed getting out of the classroom and into the ocean; it was inspiring to see how quickly they were able to learn just by being amongst the habitat rather than reading from a textbook.

With such a diverse attendance, we had to think carefully about how to make the sessions engaging and memorable. Learning through play became central to everything we did; we ended every presentation or workshop with a quick quiz or game so that the participants could win little prizes. One particular highlight was a relay race where the participants had to match words to images of different marine species that live in seagrass meadows. Everyone really let loose, running across the grass in the sunshine and laughing with one another. I loved seeing the positive energy of the communities, who were so open to learning new things.

Small actions for the future

Since the events, my colleagues and I have reflected on what we enjoyed the most. My colleague Jear (committee and secretariat) told me, “I was so impressed by how the communities learnt through doing rather than just listening, like having the chance to experience seagrass monitoring”. Like me, Roong (community liaison officer) loved seeing so much positivity:

I really appreciated the attitude of the people in the community, they really paid attention and were really prepared to understand more about seagrass. They were ready to accept support and understand any solutions that could help their lives to get better.”

During the closing workshop, the last question I asked the participants was “by yourself, with your two hands, what do you think you can do to return the benefits back to the seagrass in your daily life?”. Suggestions included clearing ocean litter, planting more seagrass, not fishing during spawning season and only using sustainable fishing gear. Nong Chananusiri, the owner of Tropical Koh Mook, the private resort on the island, said to me, “I learnt so many new things at your event. I didn’t know that the foam I always see in the water is actually seagrass pollen, so now I will be very careful not to step on it”.

Small actions like this are feeding into a culture of locally led seagrass conservation in Koh Mook and Mod Ta Noi. Now, the communities understand the ecosystem in a more holistic way and are thinking of ways in which they can give back to the seagrass to sustain it for the future.

As we talked, Kan Yaprang said to me, “I hope our village will be able to look after our natural resources by ourselves. If this happens, we will have so much more of the rich resources that we are so lucky to have right now.”

These activities are part of the Seagrass Ecosystem Services Project, managed by the Secretariat of the Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation and Management of Dugongs and their Habitats throughout their Range of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS Dugong MoU).

This project is part of the International Climate Initiative (IKI) and supported by the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) based on a decision of the German Bundestag.