The Earth Skills Network (ESN) programme is not for the faint hearted. And as Blue Ventures’ experience with ESN draws to an end, our final evaluations written and close out calls made, I’ve been reflecting on our experience of working through ESN with other African conservationists in building our leadership know-how. Strap in for a ride of self-critique and tough decision-making!

My colleagues Ny Aina, Lalao and I started the one year mentoring programme back in October 2015 in the beautiful Lajuma Reserve in South Africa’s Limpopo Province. Along with colleagues from the Wildlife Conservation Society in northeast Madagascar, and Northern Rangelands Trust in Kenya’s Laikipia-Samburu Ecosystem we worked together to analyse the management of our protected areas from a business perspective.

The BV team with their ESN mentor Felix. R-L: Ny Aina, Liz, Felix, Lalao | Photo: Liz Day

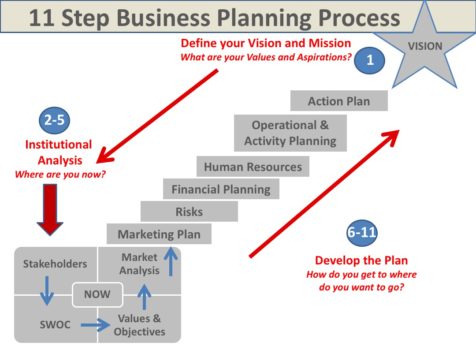

ESN 11-step toolkit | Credit: Earth Skills Network

ESN is styled around an MBA structure, ambitiously distilled into an 11-step toolkit and condensed into 10 days. The course is specifically designed for conservationists to become better managers of the socio-ecological systems in which they work. The training programme is then greatly amplified by a year of mentoring from business leaders after the initial course ends, which helps maintain momentum and provides an incentive to take action within our organisations. Having three people from our team attend helped enhance the breadth of our perspective, while increasing our opportunities for engagement with our colleagues upon our return – definitely a winning formula.

Blue Ventures’ involvement with ESN couldn’t have come at a better time, as we were starting to grapple with the operational realities of rapid growth, transitioning from a small group of field-based marine conservationists to a medium sized, multi-national, interdisciplinary social enterprise. In meetings with our mentor Felix, we used the Velondriake Locally Managed Marine Area (LMMA) as our case study. Guided by Felix, we began to scrutinise BV’s co-management of the LMMA, revealing some pertinent insights into the management of our field programmes.

From a human resources perspective, the Velondriake LMMAs is BV’s largest operational site and presented a meaty business-plan case study. Velondriake means ‘To live with the Sea’ in the local Vezo dialect, and is home to traditional Vezo fishers who live in chronic poverty, grappling with the daily realities of overfishing and a changing and hostile environment offering few livelihood alternatives.

In response to such a challenging conservation context, BV has taken a holistic and integrated approach to marine conservation, attempting to integrate a range of interventions in response to community needs including fisheries management, aquaculture as an alternative livelihood activity, community health, education, payment for ecosystems services, and ecotourism. Yet despite a clear integrated vision, the realities of running many projects across a large area, and managing a growing team had in some cases led to individual programme teams working independently. The ESN process forced us to ask ourselves to what extent was integration of programmes happening? What might be holding us back?

ESN’s process begins with an institutional analysis, and is followed by marketing, financial, operations and action planning. BV faired pretty well during the institutional analysis. We have a clear mission and strong guiding values. We also have a relatively good understanding of our stakeholders – especially the communities we work with. We’re also well aware of risks at stake and are good at promoting our mission and values through our communications and networks.

Our first big weakness was revealed when it came to the first human resources break-out session: Organisational Structure. The teams from WCS and Northern Rangeland Trust were immediately able to draw clear organisational charts whereas team BV was left looking quite clueless! This confirmed reflections we’d had in the months leading up to this programme that the root cause of the challenges we were having in integrating our programmes in Velondriake was the lack of an identified senior leader for the site overall. This is not really surprising since the layering of conservation interventions in Velondriake happened relatively quickly with new projects being built on BV’s original expedition ecotourism model in just a few years. Felix immediately saw through our problems and worked with us to draw up a matrix system organogram, which became the basis upon which we began to think about restructuring the team to better integrate our work with clearer division of management responsibilities.

Our Madagascar team has grown even more since this photo was taken in November 2015!

Fast forward 11 months and we now have an all new centralised site management structure in place, building on the recommendations of this matrix. This has not been without its teething problems, and our team in Velondriake is still refining roles and responsibilities. Nevertheless, I am positive that clearer management has already had a positive impact on our work: we’re becoming better at finding synergies in our work, helping to optimize resources and improve communication between our programmes. All this, we hope, ultimately leads to greater impact in conservation.

Will communities be willing to implement the extra management steps needed to protect ecosystems without clarity of the rewards involved? How can we better communicate the uncertainty and volatility implicit in international supply chains and carbon markets?The second weakness we identified through the process was difficulty identifying, demonstrating and communicating sustainability in the financial benefits to communities for some of our newer conservation models. BV’s approach has always been based on economic incentives to conservation, measuring and developing that impact to ensure that conservation actions make economic sense. We know, for example, that the success of the community led temporary octopus closure is due to the quick return on investment it provides, which is vital in the Vezo context. However, newer models that BV was developing at the time did not yet have this financial component clearly mapped out, which might prove problematic with longer term activities such as Fisheries Improvement Projects or Blue Carbon initiatives, which aim to reward sustainable resource management practices through seafood supply chains and voluntary carbon markets respectively. The ESN process has helped us to focus on these issues across all our programmes, and we are continuing to strive to demonstrate the practical benefits of conservation here in Velondriake – something that will be essential to keeping communities engaged in conservation efforts.

Streamlined site management and programme integration has also led teams to propose creative solutions to these issues. For instance, the further we progress with community consultations for carbon credit benefit sharing from the nascent Blue Carbon project being developed in Velondriake, the more we are finding that aquaculture and education programmes will be instrumental in pooling resources and know-how to realise community priorities including shorter term financial benefits.

The lessons learned have not been limited to Velondriake. All our field sites in Madagascar now operate within a matrix system which focuses on addressing the complex realities of the contexts in which we work. Each site now designs its own strategy (or ‘Action Plan’ according to the toolkit) knowing that all programmes will interact with one another, and impact on the communities in a holistic way.

The changes that BV has made over the last year have made Velondriake an even more dynamic and interesting place to work, and have − in my opinion − already impacted on communities for the better. I cannot recommend ESN highly enough to conservation organisations in Africa who are flexible and self-critical enough to embrace the (sometimes cringing and painful!) red flags that the toolkit raises. You can find out more, and apply for 2017 here!

A final photo of our Earth Skills Network group

The Earth Skills Network (ESN) is a collaboration between Earthwatch, UNESCO, IUCN and businesses. It connects leaders from the business and conservation communities through mentoring and skills-sharing opportunities. The knowledge gained through this global network provides new resources to help field practitioners safeguard the future of vital conservation areas.